Transmitting the Old Testament: Adventures of the Hebrew Text – Part 2

In a prior essay, we discussed how the (Hebrew) Bible gradually went from a scattered compilation of scrolls to being considered a single entity. We also discussed how the careful preservation of specific Hebrew word forms allow us to date parts of the Bible relative to one another. Finally, we discussed the Septuagint and its role as a highly regarded translation from the time of Jesus down to the present day. In the present essay, I would like to consider the Dead Sea Scrolls and how they help to broaden our understanding of the Hebrew text of the Bible. Read Part 1

Some decades before the birth of Jesus, a group of Jews left Jerusalem due to conflicts with the High Priest over aspects of religious observance and leadership. This group was puritanical in nature and apocalyptic in their expectations for the world, believing that they should withdraw from Jerusalem for a time after which God would set the world right. Among other things, this group expected that ‘true’ worship would be restored at the temple and their leader would be instated as the High Priest. The group’s chosen place of exile was Qumran (possibly Secacah, see also Joshua 15:61), a small settlement near the coast of the Dead Sea and about 25 miles southeast from Jerusalem. Both the group and their beliefs would have been lost except for a surprising discovery there in 1947: small caves near the Qumran settlement were found to contain scroll fragments, some of which contained portions of the Bible. The most significant of these caves is pictured below:

This discovery was termed the ‘greatest archaeological discovery of the twentieth century’ by William Albright, the leading scholar who authenticated the scrolls. Albright certainly had a point—for several reasons. I will discuss three of these reasons below.

The first reason involves the complicated relationship that the Septuagint has with the Hebrew Old Testament. To understand this reason more fully, it is necessary to give a bit of background. The oldest known Hebrew Bible text in existence, up until the Dead Sea Scroll fragments were discovered, was written in the early part of the 10th century CE. This text is typically referred to as the Masoretic Text (more about this text in the following section).

The tenth century date had been a bit of a sore point for academics who work on Hebrew manuscripts, in part because there are two Septuagint manuscripts that date to the fourth century (Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus) along with another dozen or so Greek Bibles from the fifth to the ninth centuries—all which significantly predate the oldest Hebrew Bible from the tenth century. This is a bit like a Shakespeare aficionado being required to learn French to read the oldest copies of Hamlet! It seems backwards.

Perhaps this strange state of affairs—with the Greek translation being older than its Hebrew parent—would not have been a problem except that the Greek and Hebrew versions of the same passages sometimes differed (most notably in Jeremiah). To some, such differences meant that the Hebrew text, being the more recently copied, probably belonged to a textual tradition which had been amended/corrupted sometime after the Septuagint manuscripts had been copied from Hebrew. There was no firm proof for this claim, of course, but it is easy to understand why someone would have suspected some sort of textual emendation.

Making matters more emotionally charged, and in spite of the fact that the Septuagint had been translated by Jews, the Septuagint gradually had become the Bible of the Christians, while the Jews read either the Hebrew text or Aramaic translations (called Targumim). In effect, this pitted Christians against Jews, each with their own version of the Bible. While this did not mean that Christians ceased to value the Hebrew, those Christians of a more antagonistic bent sometimes accused Jews of amending the Hebrew text to better accord with anti-messianic views. Jews, likewise, were suspicious of the value of a translation that had long since ceased to be used by their communities.

However, upon the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, it was learned that a text very similar to the tenth century Masoretic Text had existed already from the time of Jesus. In practice, this meant that, rather than the Septuagint being superior to the Hebrew, the reverse was frequently the case. The Septuagint was different because the translators, at least sometimes, were not as accurate in their work as they could have been. (Here, I am passing over many important details, but I think that, after all necessary caveats are explained at length, I am still characterizing the situation with due fairness.1)

We now turn to a second reason that the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls was significant. In a few limited instances, the scrolls provided new information regarding the biblical text. Perhaps the most interesting of these discoveries concerns Nahash the Ammonite (1 Sam 10-11). First Samuel chapter ten describes the anointing of Saul; chapter eleven, the defeat of the Ammonites at the hands of the recently anointed King Saul. In Qumran Cave 4 (pictured above) fragments of a scroll of the book of Samuel contained some information that bridged the two chapters, in effect ‘new’ words of the Bible that had lain forgotten for two thousand years. An English translation2 of the relevant text is as follows. The italicized portion reflects the previously unknown information from scroll 4QSama:

10:26. Saul also went to his home at Gibeah, and with him went warriors whose hearts God had touched. 10:27 But some worthless fellows said, “How can this man save us?” They despised him and brought him no present. But he held his peace. Now Nahash, king of the Ammonites, had been grievously oppressing the Gadites and the Reubenites. He would gouge out the right eye of each of them and would not grant Israel a deliverer. No one was left of the Israelites across the Jordan whose right eye Nahash, king of the Ammonites, had not gouged out. But there were seven thousand men who had escaped from the Ammonites and had entered Jabesh-gilead. About a month later, 11:1. Nahash the Ammonite went up and besieged Jabesh-gilead; and all the men of Jabesh said to Nahash, “Make a treaty with us, and we will serve you.” 11:2 But Nahash the Ammonite said to them, “On this condition I will make a treaty with you, namely that I gouge out everyone’s right eye and thus put disgrace upon all Israel.”

1 Samuel 10:26-11:2, with the addition from 4QSama

It is remarkable how well this extra bit of information about the intimidation tactics of Nahash helps to fill out the story’s details. We can now understand why the men of Jabesh-gilead were cowed as readily as they were: they knew that their goose was already cooked.

As the above ellipsis occurs between the two occurrences of the word Nahash, what probably happened is this: the scribe who accidentally omitted several lines of the text reached the first occurrence of the word Nahash in his exemplar, copied it, and then returned to his exemplar looking for the word immediately following Nahash. But, rather than returning to the first occurrence of Nahash, his eye accidentally caught the second occurrence and he proceeded with his copying from there. As the text is not unreadable without this short paragraph, the ellipsis was never caught and the mistake was subsequently copied into other manuscripts with no one the wiser.

Corroborating this reconstruction that I have outlined, Josephus (1st century AD Jewish historian) includes some of the details of 4QSama in his writings, meaning that the scroll of Samuel to which Josephus referred also contained these verses. In summary, the Qumran scrolls sometimes appear to have information regarding the biblical text that was very nearly lost. Naturally, this makes their discovery all the more important.

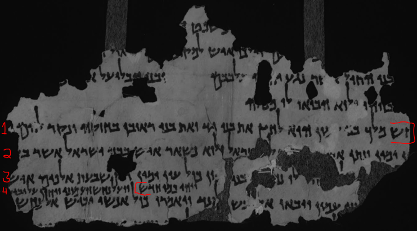

The following image shows the Qumran (4QSama) fragment with the additional information about Nahash.3

Qumran (4QSama) fragment. (The red brackets show where the extra information begins and ends. There are three full lines worth of text, with a fourth line inserted interlineally—as can be seen by referring to the numbers on the left.

It should be noted that the example of the Nahash ellipsis is a usual one. In most cases, the biblical scrolls at Qumran contain few, if any, surprises. This confirmation of the by and large accurate copying of the Hebrew text is a third reason why the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls is important.

Once again, we begin with an illustration in English that can help us understand the Hebrew text. To wit, American English spelling does not always agree with British English spelling: realize/realise, meter/metre, gray/grey, mom/mum. In instances such as these, the spelling conventions are only clear because the respective countries publish their own dictionaries stating what the proper spelling is supposed to be. (And I, an American currently living in the UK, have been required to adjust my spelling accordingly!) But, in a world where no such dictionaries exist, spelling choices are not entirely fixed. Even Shakespeare, with his remarkable grasp of English, spelled his own name in a number of different ways. In short, without dictionaries, spelling convention will inevitably tend towards fluidity. There is no one right way to spell a word.

Such is the case in the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible. Words which are spelled in one way at one place may be spelled differently at a second place. Sometimes variation occurs within the same book, and even within the same chapter. Some books favor one spelling, and some books favor another. There is no way of knowing ahead of time which spelling will occur where.

In spite of this ostensibly casual attitude towards spelling, a surprising number of the Dead Sea Scrolls mirror the spellings of the Masoretic Text on a case by case basis. This means that the generations of scribes which link the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Masoretic Text were remarkable copyists. This is to say, one should not begin by assuming that scribes were careless. In most cases, they did their work with surprising faithfulness.4

To be continued…

ENDNOTES

1 In the case of different versions of Jeremiah, it should be noted that the Septuagint’s version is probably older than the Masoretic version, although likely not by many years. This issue is quite complicated, as I mentioned above. Return to context⬏

2 NRSV. Return to context⬏

3 Plate 1096, frag 6; B-368589. To see the image for yourself, go to https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/explore-the-archive/image/B-368589 Return to context⬏

4 Again, I am omitting a significant amount of information, but trust that my characterization will be judged as accurate. Return to context⬏

Leave a Reply